Ever had your work ripped to shreds during a critique? Do you remember the feeling of embarrassment and shame? If you feel these things, then it was the critique that was a fail. Not You. The purpose of critiquing work is to gain feedback to improve not only your project, but your writing technique as well.

Giving constructive criticism is challenging but not impossible. Changing your attitude toward critiquing will help you get to the most important feedback for the piece. Not just typos and inconsistencies, but help with tone, voice, plot arc, character development, and more.

It sounds like a lot, but not if you break it down into bite size portions. First, you will need to make sure your group has spelled out the basic ground rules for the critiquing session.

Speak the Truth

Jennie Nash wrote a guest post for Jane Friedman on the dangers of writer groups. She provided some excellent ideas of how to turn the empty remarks that often come out of a writer’s group critique session into helpful feedback. Her specific advice was:

- Every writer in your group needs to agree to speak the truth and to accept the truth.

- Each member needs to speak with deep kindness and a sense of hope when it’s their turn to offer a critique.

- Each member needs to take a deep breath and welcome the truth when it’s their turn to hear it.

These ideas are the perfect basis for a good critique session. Now that we have some ground rules for a good critique session, let’s move on to the criticism itself.

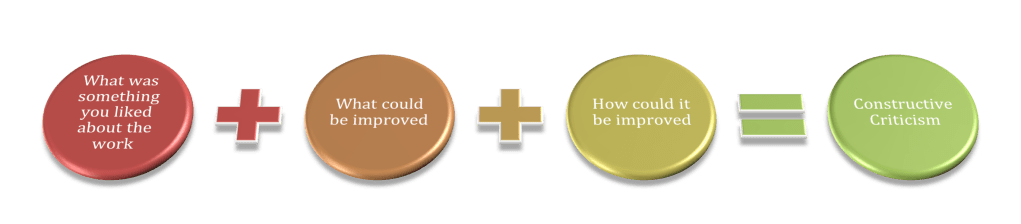

For effective constructive criticism, remember this equation.

Provide Positive Feedback

The power of positivity is not to be forgotten. I worked for a leadership development organization, Zenger Folkman years ago. I have never forgotten their basic strengths-based approach to leadership. They work on the philosophy that instead of concentrating on improving our weaknesses, we should instead focus on our strengths. The weaknesses will often follow suit in the improvement process.

While we are not assessing leadership and personality strengths, the philosophy still applies to constructive criticism. Focus on what is good about the piece you are critiquing instead of nitpicking the negatives. Even if you hated the piece, there is always something to praise.

Lift up the writer with examples of what they did well so they know to emulate those techniques in the future. Some questions you could ask yourself as you prepare to provide constructive criticism are:

- Was the overall premise interesting?

- Even if you didn’t like the subject, was it clearly articulated?

- Did you feel any depth with a particular character?

- Was the tone and voice of the piece consistent?

- Were you able to follow the characters’ actions?

Points of Improvement

After providing at least one positive, it is time to begin tricky part of the criticism. What do you feel could be improved upon? Remember, this is not a list of what the writer did wrong. This is an opportunity to provide insight for not only the writer, but the other writers who are participating in the critique session.

How can you express a negative in a productive manner? Be specific in a non-accusatory way when explaining the problem. Let’s look at an example. You have read a piece and really dislike a character. Instead of saying:

“I really hate this character.”

Try to be more specific about why you dislike the character. For example:

“The character feels flat. I’m not feeling any emotions about them. That’s a problem”

Being more specific helps you identify the problem instead of giving vague feedback. You are talking about the writer’s baby. Lift them up with useful information instead of subjective comments.

What kind of things could you look for when assessing a piece? Here are some ideas of what to look for:

- Was the beginning effective in grabbing your attention?

- Could you identify with the characters on some level?

- Was there enough information about the characters to give you an idea of who they are?

- Could you identify the setting, or did you feel like you were in a vacuum with the characters?

- Did the voice of the piece match its overall goals? Was it too serious for the subject matter? Too casual? Too comical?

- Did the point of view stay consistent? Was the narrator head-hopping?

- Did you feel the necessity of the scene?

Propose a Solution

When bringing a problem to the table, always attempt to bring a potential solution with it. You are not telling the writer how to write or what to do, you are giving advice from your knowledge.

It’s okay if you don’t know how to fix the problem you found. Another in the critique group might have the answer. You are not opening the floor for discussion but expressing the possibility that both you and the writer can find wisdom within the group.

Being honest and open about your lack of knowledge means your group has identified a topic worthy of more study during the lesson portion of your meetings. If you have the question, someone else probably does, too.

Conclusion

Following the equation is vital in providing truly constructive criticism. Provide positive feedback, be specific about places for improvement, and propose a solution whenever possible. It’s okay to be brutally honest (not hurtful or malicious) with your constructive criticism as long as you give the writer constructive feedback they can use to improve their work. That is the real reason for critiquing our work in the first place. To help each other grow and improve.

Comment below with what you think is the most important rule when critiquing.